Winter is in full swing in the capital, with daytime temperatures dipping below 20°C. Ironically, that’s also when Delhi’s tourist spots see their biggest turnout. The smog-and-cold combination often makes me think staying home is the smarter plan. But in the eternal confrontation between my lazy self and my wanderlust-bitten self, it’s usually the latter that wins.

This Sunday, INTACH organised a walk at the National War Memorial, led by raconteur Dr Shahjahan Avadi—an ex–Air Force officer himself. The memorial is located near India Gate, and my logical self did know that parking would be a problem. But it was cold, and I decided to take the car anyway.

The drive up to the oddly named C-Hexagon circle was smooth. And then I joined the queue to enter the Central Vista parking and immediately realised that getting the car was not a bright idea. Thanks to a fellow walker, I managed to find a spot nearby.

Then, what should have been a simple walk to the statue of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose turned into a brisk walk—and then a jog—as we searched for the entry. My rant about signage has now become a constant at most public locations in the country. After a brief hunt through the sea of humanity around India Gate, we finally located the group.

Built in 2019, the National War Memorial honours India’s fallen soldiers. Designed in concentric circles, it is said to echo the ancient war formation of the Chakravyuh.

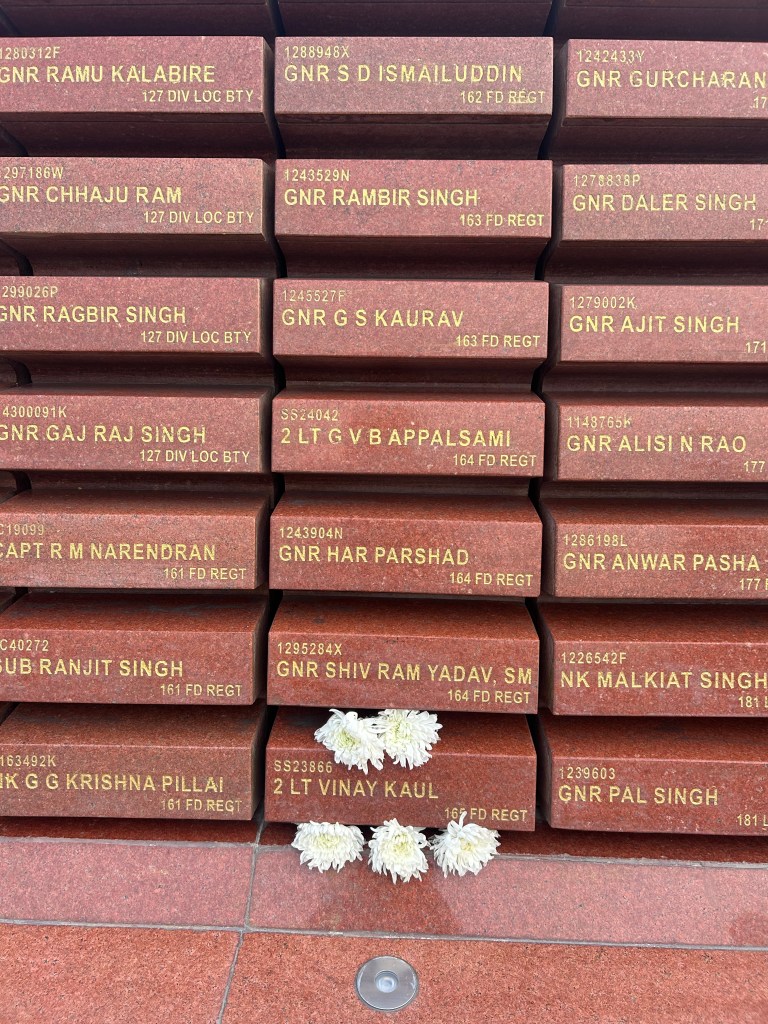

The first circle is the Raksha Chakra, a ring of trees symbolising the stability and integrity of the nation. Next comes the Tyag Chakra, where granite panels bear the names of those who made the supreme sacrifice—etched in golden letters. From 1947 to the present day, the names of martyrs can be read here.

As we walked, something caught my attention: someone had placed flowers at two granite panels. It made me wonder how often we truly think about these sacrifices when we think of our country. We celebrate achievements—and rightly so—but do we pause to consider whether those achievements would have been possible without the lives given, and without the soldiers who continue to guard our borders?

We then moved to the Veerta Chakra, which houses murals of battles that became turning points in the nation’s story. From Tithwal to Rezang La, from Longewala to Gangasagar to Meghdoot—each mural carried a reminder of indomitable courage and enduring sacrifice. It was heartening to see that even amidst the India Gate crowds, many were drawn into the quieter gravity of the memorial. These stories deserve to be known by more people.

At the centre is the Amar Chakra, where the eternal flame burns—Amar Jawan Jyoti. Beside it is a cabin where a soldier stands guard in honour. The discipline is so absolute that for a moment we almost mistook him for a statue. Being a Sunday, we also witnessed the change of guard and the retreat ceremony.

As dusk settled, the flames around Amar Jawan Jyoti were lit. An elaborate change of guard followed, and finally the five flags—the National Flag and those of the Army, Navy, Air Force, and IDS—were lowered. By the time the ceremonies ended, the air had turned sharply cold. Pulling my fleece tighter, I remembered a story Dr Avadi shared about Operation Meghdoot—how he said one can lose around 10% of one’s memory after serving in Siachen.

It was a Sunday well spent—learning a little more about the bravery, courage, and quiet determination of our armed forces.