In our fast-paced world, there are moments when a sight or a sound takes you back, when life feels lived, not rushed. I belong to that in-between generation that grew up analogue and stepped into digital adulthood. Lately, I’ve found myself pausing more often, trying to catch my breath in the whirlwind of the way we live now.

About a month ago, over dinner at The Kunj, Chef Sadaf Hussain remarked that Delhites won’t wake up early for nihari. This week, an email landed in my inbox about a food walk in Purani Dilli, enticingly titled “Nahari and Nashta” by Tales of City, led by Chef Sadaf. It began at 10:00 a.m. Manifestly, Delhites were not trusted to wake up early.

Purani Dilli, for me, is where centuries coexist. It’s also the part of the city that makes me more curious the more I see. So on Saturday morning, braving the cold and the fog, I joined a group of fellow foodies outside Gate No. 1 of Jama Masjid. The city was wrapped in mist, but it was awake; the area was already crowded. You could sense preparations for Ramzaan beginning.

Maneuvering through winding lanes, we reached Shabrati, a small joint with a big reputation for serving truly delicious nahari. Now, I’ve always called it nihari. It was only today that I learned it is actually nahari, a dish eaten at nahar, or dawn. Traditionally, food for the masses, sold on carts across the old city, it was later adopted by royalty. We huddled inside the compact eatery and dug into nahari with khameeri roti. Soon a quiet descended, the kind that arrives only with good food, punctuated by extra servings and satisfied, happy nods.

Tea followed, of course. Standing outside Shabrati, we spoke about the journey of food as we know it, from the 14th century onwards. As we were about to move on, we noticed the kitchen preparing nahari for the evening. While we clicked photos, Chef Sadaf tried his hand at stirring the enormous handi. It was quite funny to watch the chef at the eatery look on with deep suspicion, apparently not trusting another chef to stir it “properly.”

We moved through more lanes, past vendors selling offals by the side. The scene reminded me of growing up in Arunachal, when the local butcher would inform my father if good mutton had come in. Mutton was always bought in person. The foodie and brilliant cook that my father was, he would decide what he wanted to make on Sunday and choose the cuts accordingly.

At Sheeren Bhawan, as our discussion drifted towards sugar and its journey across the world, a pale, creamy halwa arrived. On the counter lay a whitish tuber. It turned out to be safed gajar or white carrot, an indigenous variety, more fibrous than the popular red one, and the halwa was made from it. It was the first time any of us had even seen a white carrot, let alone tasted halwa made from it.

As we moved through the maze of Purani Dilli, a slower slice of life revealed itself, unhurried, detailed, and oddly comforting. A store selling betel nuts and the condiments necessary for paan. A Rafu Ghar, almost extinct in today’s use-and-throw world, a skill fading into memory. A shop selling only parathas. An ear cleaner. And then there were the lane names, quirky, specific, sometimes poetic, offering glimpses into the trades that once populated these streets.

We reached our next stop only to learn we were late: the nagori halwa was over. But bedmi puri and aloo ki sabzi more than made up for it, as we spoke about the deep connections between communities and food, how recipes travel, adapt, survive, and become identity.

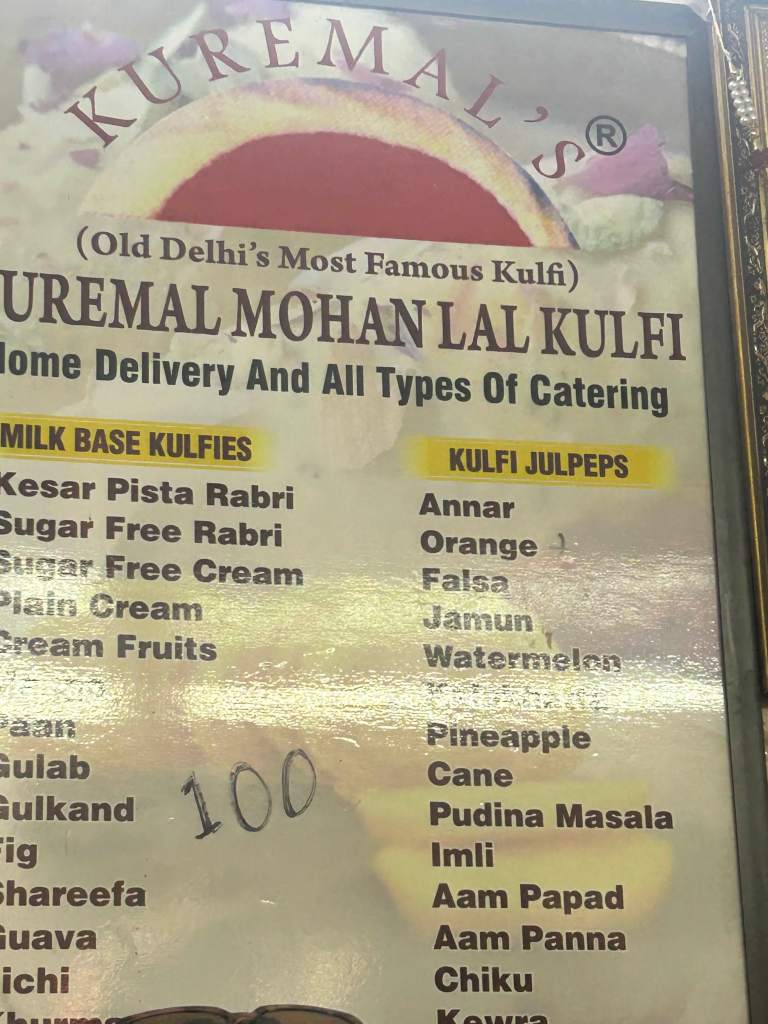

The walk ended at one of the oldest kulfi shops in the city, and once again the word Julpep made me smile. Talking about spices, culture, and the influence each has on the other, we relished different kinds of kulfi. My favourite, of course, was the Santara kulfi.

When I entered Chawri Bazaar Metro Station and boarded the train, it felt like I was travelling not just out of Purani Dilli, but from a slower life into a faster one. Yet the hours spent that morning, on food, yes, but also on absorbing a culture of coexistence, were perhaps the best kind of weekend reset I could have planned.