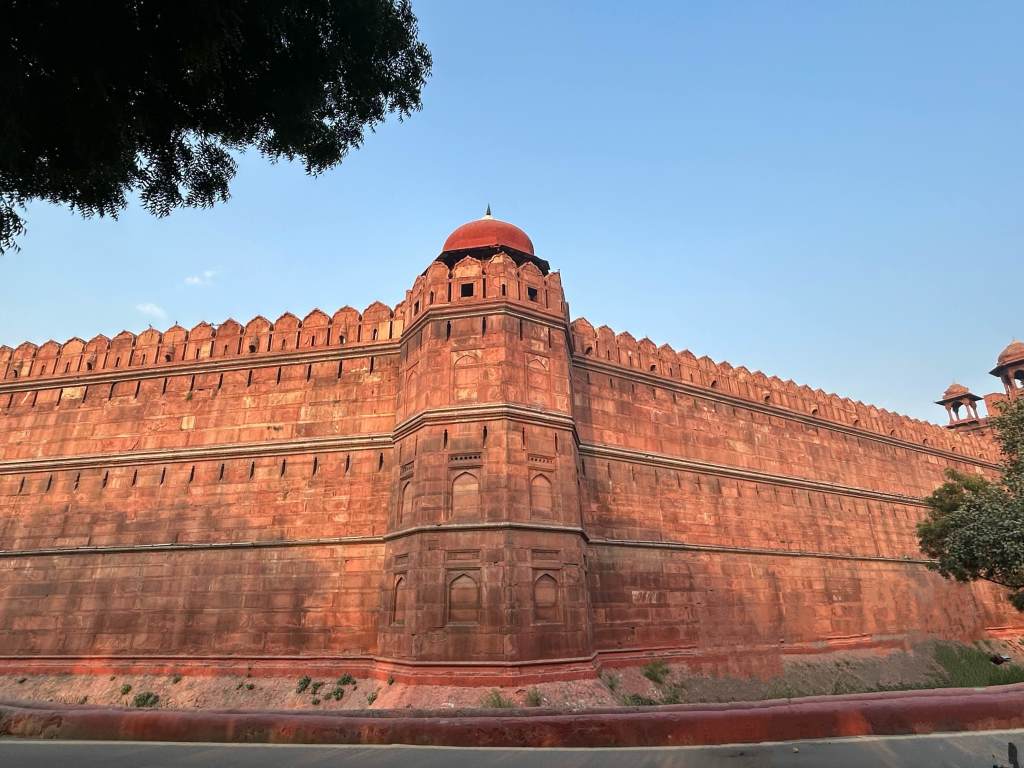

There is something about the Red Fort—maybe because every time I have seen photographs or a telecast of Independence Day or Republic Day, it is the Red Fort that comes into view: stately, majestic, almost like a witness to everything that has unfolded around it.

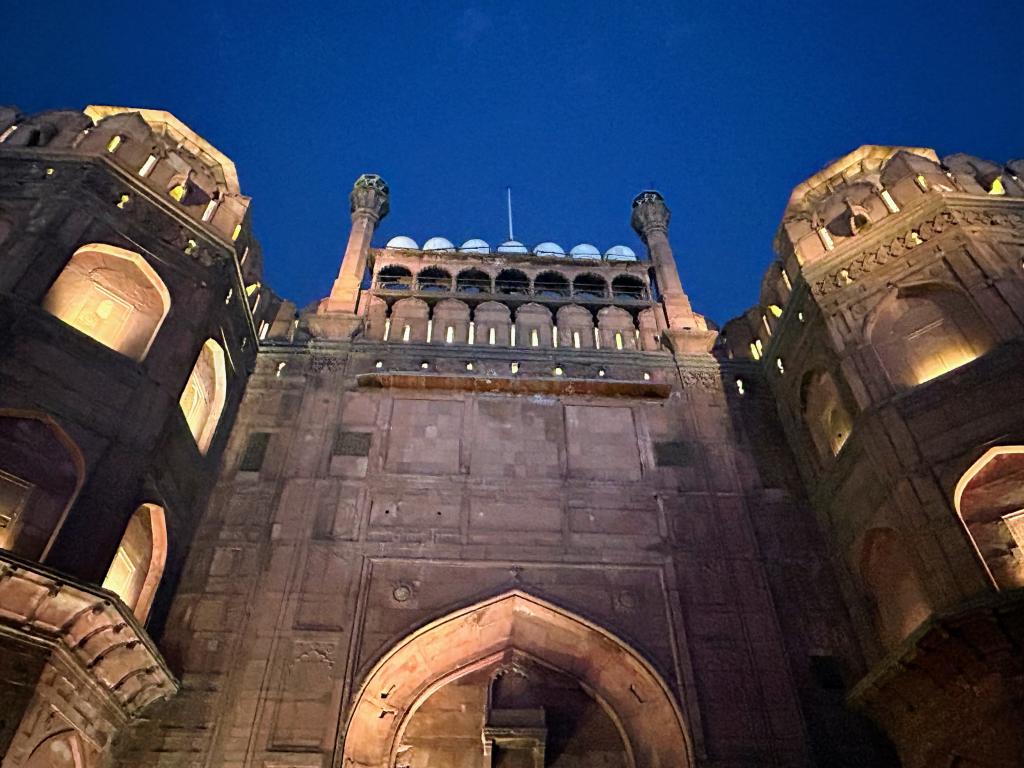

So when an INTACH email landed in my inbox about a heritage walk at the Red Fort this Sunday, I had to join. Delhi Metro is the best bet to reach anywhere on time. The crowd I encountered while changing trains at Kalkaji should have warned me of what was to come. At Lal Qila, I emerged from the gate and realised it was almost a sea of humanity. Somehow, manoeuvring through it, I made it to the entry near the Lahori Gate.

Our walk leader, Javeria, had to shout just to make herself audible. Unfazed, she led us through the crowded spaces, sharing insights not only about history but also about architecture. We entered through Chatta Chowk—one of the earliest covered markets of its time—crossed the Naqqar Khana, and reached the Diwan-i-Aam.

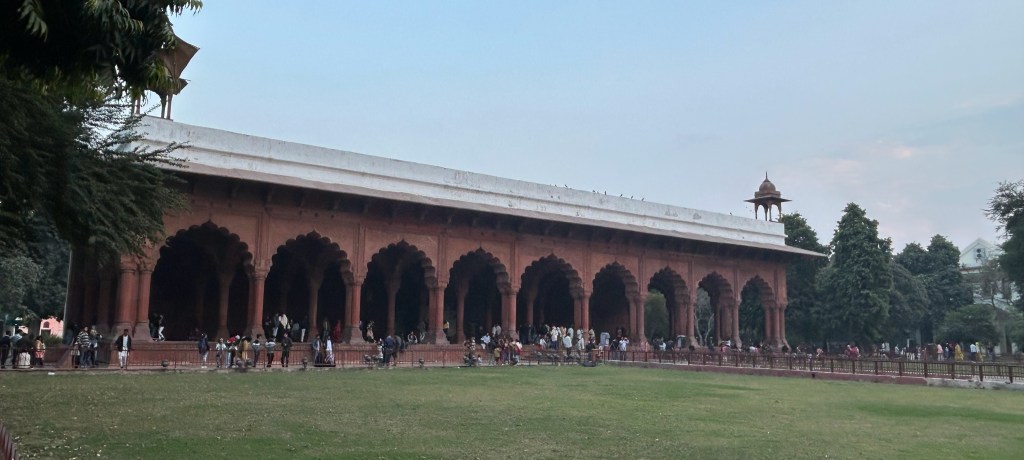

Whenever I visit forts, I find myself wondering how people lived there. How was each place used—really used, day after day? The Diwan-i-Aam is stately, and the contrast of red sandstone with the highly embellished throne stands out. But it was a small detail that shifted everything for me: hooks on the ceiling outside, used to hang curtains—muslin or velvet depending on the season. That single observation triggered my imagination more than any grand façade could.

As we paused at the corner of the Diwan-i-Aam, the fort’s hierarchy became visible in stone. The areas meant for nobles and royalty were built in Makrana marble. The fort is said to have been constructed at a cost of six lakh rupees—a princely sum, and a sizeable figure even today. But we are speaking of a period when the Indian economy was possibly booming in ways we rarely pause to remember.

The first marble building we encountered was the Rang Mahal, a palace for the emperor’s concubines. An elaborate fountain system—run only by gravity—greets you there. I found myself wondering who the architect of the fort was. Imagine my surprise when Javeria mentioned it was the same architect associated with the Taj Mahal. And then the old story surfaced in my mind: wasn’t his hand chopped off so he could never build anything again? Apparently not. History, like memory, collects myths the way monuments collect dust.

We moved on to the emperor’s sleeping quarters. There is a barricade on the steps so people don’t climb them now, but you can still see a depression where the marble has slowly worn down with regular use. These quarters were never meant for mass entry. Today, most of the marble spaces can only be seen from outside—beauty held at a distance.

The lawns were being readied for an evening programme, ticketed. The security guards were almost shooing everyone out. But then, they underestimated our curiosity. We stopped near the pavilions to look at the Zafar Mahal: a red sandstone structure constructed by the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar. It stands out for its bare, un-embellished walls—a quiet testimony to the loss of power of the Mughals.

On our way out we saw the barracks built by the British after 1857 to house soldiers. The question came automatically: where did soldiers stay earlier? Javeria pointed out that rooms within the fort walls were used for them. What struck me even more was another fact: only the emperor stayed in the fort. Even his sons and daughters were not allowed to live there. The power of intrigue, deceit, and politics—clearly—has existed in all times.

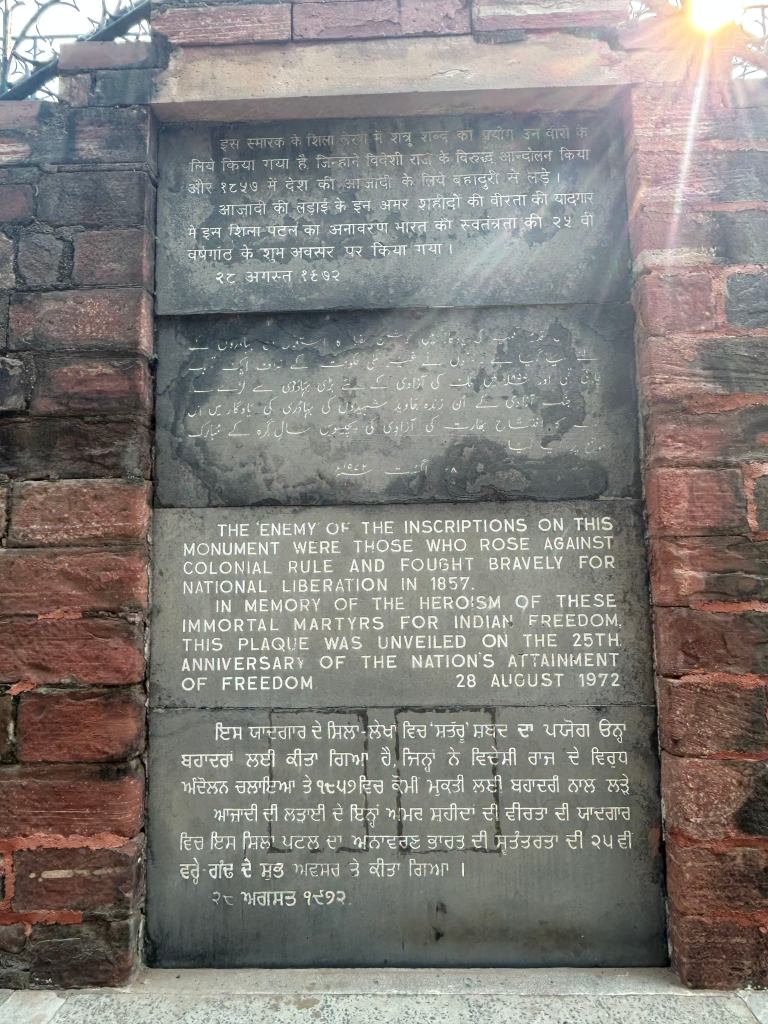

By the time we left, the crowd had thinned. For the first time that day, one could stand at the entrance and simply marvel at what the fort must have proclaimed in its heyday.

I looked up at the lit ramparts and realised the fort would pull me back again. The child who watched Republic Day parades on television, spellbound, is not yet satisfied. Until the next time, the Red Fort will remain what it has become for me: a medieval icon adopted by a modern nation.