Conversations at Work and Cultural Crossroads

One of the joys of being in a diverse workplace is the daily discovery of traditions, rituals, and stories that colleagues carry with them. Over cups of tea or during lunch breaks, conversations turn into cultural exchanges — each person explaining their customs, sometimes teasing one another in their mother tongue, and often leaving everyone a little wiser.

A few weeks ago, I overheard a conversation between two colleagues — a Bengali and a Punjabi. The Bengali was explaining Mahalaya to the Punjabi. For most, Mahalaya simply marks the ending of Pitru Paksh across India. But for Bengalis, it means much more: it is the dawn that ushers in Durga Puja, the most awaited festival of the year.

The Unmistakable Voice of Tradition

For anyone who is not Bengali — and has never heard Birendra Krishna Bhadra’s baritone narration — it is difficult to explain what makes Mahalaya so special. Since its first broadcast in 1931, All India Radio’s iconic programme Mahishasurmardini has become synonymous with the day. Scripted by Bani Kumar, set to music by Pankaj Mullick, and enriched with devotional songs by some of Bengal’s finest singers, the programme’s heart lies in Bhadra’s voice reciting the Chandi Path.

Generations of Bengalis have woken at dawn on Mahalaya to listen to this. The music, the chants, and above all, Bhadra’s voice signal that Durga Puja is just around the corner.

Childhood Rituals and the Magic of Radio

My own memories of Mahalaya go back to childhood. A day before, my father would carefully tune the radio to catch the AIR frequency and then place it by the bedside. An alarm was set for 4 a.m., and when it rang, I would awaken not to the sound of a bell but to Bhadra’s sonorous voice filling the room.

Later, when cassettes of Mahishasurmardini became available, families eagerly bought the two-cassette set. It meant one could listen anytime, without waking up before dawn. Yet, the cassettes never quite captured the magic. The ritual of rising in the pre-dawn darkness, with the crackle of the radio and the collective stillness, held its own irreplaceable charm.

When Change Met Resistance

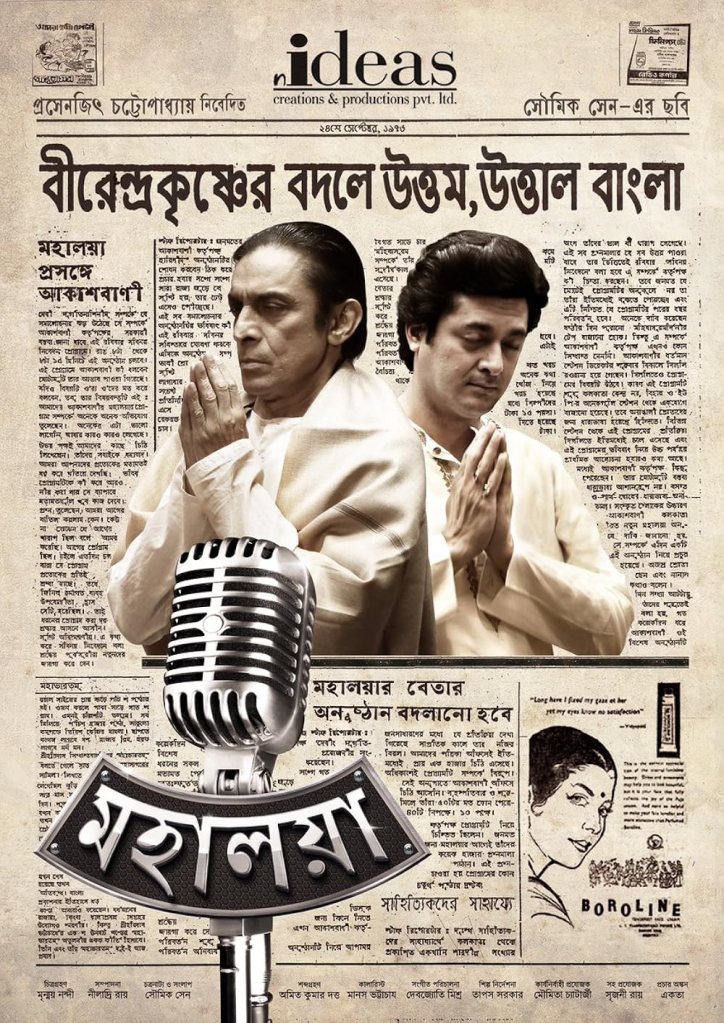

Technology wasn’t the only agent of change. In the late 1970s, when Uttam Kumar reigned as the Nayak of Bengali cinema, All India Radio attempted to recreate the programme. With narration by Uttam Kumar and music by Hemanta Mukherjee, the new version was expected to captivate audiences. Instead, it sparked a massive backlash. For listeners, replacing Bhadra’s voice felt like sacrilege. The experiment failed, and AIR never tampered with the original again.

For my family, this story carried its own humour. My mother, a devoted Uttam Kumar fan, was disappointed, while my father — who never cared much for Uttam’s acting — recounted the “failure” with a gleeful chuckle every year. Decades later, the controversy found its way onto the silver screen in the 2019 film Mahalaya.

Rituals in a Changing World

Today, the world is very different. Technology has transformed how we consume tradition. Yet, Puja is the anchor of a Bengali’s calendar. Yesterday, I went to CR Park, the hub of Bengalis in Delhi, and it was almost as if I had been transported. A book fair, a saree mela juxtaposed with cultural performances seemed to signal that Pujo had begun.

This morning, I found myself using the Spotify app at 4 a.m. and beginning my day with Bhadra’s immortal narration. The medium has changed, but the ritual remains.

As Uttam Kumar’s character says in the film Mahalaya: “Birendra Krishna Bhadra’s voice is Durga Puja.” Indeed, for Bengalis everywhere, the festival begins not with the idol-making, not with the lights or the pandals, but with a voice — deep, resonant, and timeless — announcing that the Goddess is on her way.

‘Maa asche’